Tristian Morton took a deep breath and then climbed onto the platform.

He didn’t think about the other swimmers. He didn’t think about everybody in the stands. He didn’t think about the millions of people watching on TV.

With such intense focus that he didn’t hear the referees yelling for the swimmers to take their place, Tristian saw seven of the best swimmers in the world get ready and then he tip-toed to the edge of the small square diving platform.

Over the past four years, he’d spent more time in the water than on land – preparing and qualifying for the grandest peak of competitive swimming.

He had advanced through the heats and semifinal earlier, landing him in the finals of the 100-meter freestyle. Now there were only eight men chasing what every swimmer in the world coveted. A Frenchman was in the lane on his left and an Australian was on his right.

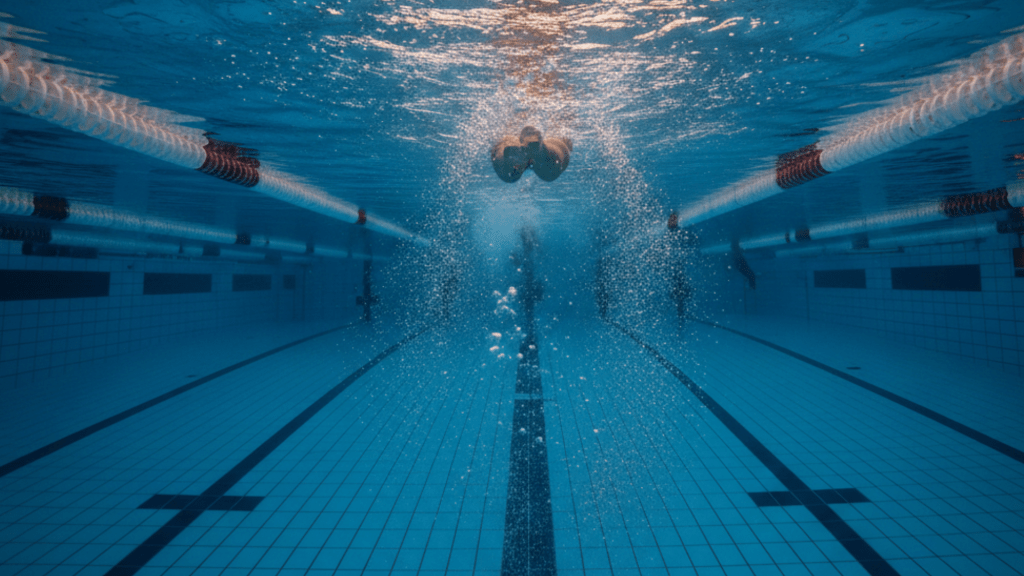

The starting horn sounded and Tristian aggressively dove into the pool.

The water provided little resistance as Tristian sliced through it like a porpoise. He swam several meters underwater, which acted like a soundless void – complete silence as he wiggled through the water, before he broke the surface and heard muffled cheers.

For more than twenty seconds his arms were steam-powered machines windmilling through the water. He prepared for the critical turn halfway through the race – oftentimes this moment decides who wins.

Tristian didn’t know his time. Was he in first place? Last place?

He was surprised how little he cared.

* * * *

Tristian walked into the hospital room behind his mother.

As a 9-year-old boy, the room scared him. He didn’t like how it smelled or how everybody in the entire hospital seemed so sad. Tristian didn’t want to go inside Room 46, but his parents said it was important. He had to be a big boy, his mother said.

Walking behind her, Tristian only saw his older brother’s toes sticking up under a blanket – but he heard a strange noise.

Beep … Beep … Beep … Beep.

Ellis Morton’s eyes were closed and he had a tube in his mouth and another coming out of his arm. Their dad sat in a chair in the corner with his head tilted back and his eyes closed. Tristian’s teenage sister, Samantha, sat in another chair in sweatpants with no make-up. She looked more angry than tired.

“Ellis, look who’s here to see you,” his mother softly said.

Of course, Ellis didn’t say a word. Or move. Or do anything. He simply laid there with his eyes closed.

“Did you want to say anything to Ellis, sweetheart?” Tristian’s mother said to him. “I’m sure he can hear you.”

Tristian turned away from Ellis and grabbed his mother’s waist as tight as he could. She rubbed the young boy’s back and told him it was okay. He didn’t need to say anything if he didn’t want to.

Tristian mumbled something into his mother’s skirt and she asked him what he said.

“Is he okay?” Tristian cried.

His mother didn’t know what to say to that, so she made a nondescript noise.

“He’s gonna die, Tristian!” his sister snapped.

“Samantha!” his mother yelled back.

“What? It’s true! He’s gonna die! The doctor said too much water was in his lungs for too long. He’s gonna die, Mom!”

Their mother had Samantha leave the room, which she happily did. After his sister stormed out, Tristian turned back around to look at his brother. He asked his mother what he was supposed to say and she told him to say he loved him.

Tristian nodded but he couldn’t stand to look at his dying older brother. Instead, he turned his head to look at Ellis’ feet pointing up at the ceiling through the blanket.

“I love you, Ellis,” Tristian said softly.

Beep … Beep … Beep … Beep.

* * * *

Tristian made his turn flawlessly, pushing off the wall and speeding back underwater toward the finish with the power of a speed boat. Bursting through the surface once again, his arms circled violently through the water, pushing him closer and closer to the finish.

With only ten meters remaining, he assumed some of the swimmers had already finished – they were probably celebrating and splashing through the water like children.

Just keep going, he thought. Just keep going.

He reached his arms as far as he could and then finally finished, the momentum throwing his body against the hard wall.

Tristian didn’t look up at the crowd or check his time. He sensed chaos all around him but he couldn’t hear any of the cheers. He only heard that familiar sound in his head.

Beep … Beep … Beep … Beep.

He felt somebody smack his back, so he looked over and the Australian smiled widely. The Aussie said something. Tristian furrowed his eyebrows because he couldn’t comprehend what the man said.

“What?” Tristian asked.

“I said, congratulations, mate! Incredible!” the Australian said and pointed up at the scoreboard, which caused Tristian to look:

Morton – USA – 46.05

He not only won. Tristian had set an Olympic and world record.

“An honor to be in the lane next to you, mate!” the Australian swimmer yelled.

After all the racers got out of the pool, Tristian was escorted away with two other swimmers, including the Australian. Ten minutes later, somebody from either the International Olympic Committee or NBC’s production team motioned the smiling Australian toward a podium, where he received a beautiful bronze medal.

Then the person pushed the other swimmer toward the podium, a Dutchman who did not smile when he got his silver medal. Finally, the person pushed Tristian in the lower back toward the podium. He climbed up to the highest step and bent over slightly as an older man put a gold medal around his neck.

He stood up straight without a smile.

When the TV reporter interviewed him later, they asked Tristian why he wasn’t smiling. He won an Olympic gold medal, for goodness sake. Why the blank expression?

“Oh, it was so surreal,” Tristian lied. “A small-town kid like me winning Olympic gold? I didn’t know what to do because I still can’t believe it.”

The truth is he hoped the moment would make him happy. To finally have a reprieve of the darkness. To look at the shiny gold and feel that Ellis was proud.

But even with the achievement of a lifetime, he still couldn’t shake the guilt.

He couldn’t stop thinking about when the beeps stopped in the hospital room.

* * * *

“Get away from there!” Ellis yelled at Tristian.

The 18-year-old Ellis led an adventure outing with Tristian and the rest of the church youth group. Ellis and twelve boys between the ages of eight and ten enjoyed an expedition along a bluff and they were nearly at the end of a two-mile hike to a plunge pool, where everybody eagerly anticipated a summer swim.

Tristian walked over to the edge and looked down at the water seventy feet below, which caused Ellis to yell at him. Tristian yelled back that he only wanted to look – he was curious because that’s what 9-year-old boys are. Curious.

“I don’t want you falling in, since you don’t know how to swim because you won’t let me teach you,” Ellis snapped back in front of all the other boys, which embarrassed Tristian.

Normally young boys worship their older brothers, but Tristian resented the attention Ellis got for his swimming prowess. He was the small town’s star high school swimmer – even finishing fourth place at the state meet. For that, they hung a banner with Ellis’ name in the high school gym. As his family and everybody in town showered Ellis with praise, Tristian felt invisible and swore he’d never learn how to swim.

As protest.

Looking over the edge of the bluff, Tristian was about to shout back that Ellis was being like their mother, when he slipped on a wet exposed tree root, stumbled forward, and screamed as he fell down to the water.

“Tristian!” Ellis cried.

The older brother instinctively took off his backpack and jumped off the edge. The impact from the water broke Ellis’ ribs, and he frantically swam underwater toward where he thought Tristian was. For more than 20 seconds, Ellis’ heart raced as he thrashed his arms and legs to feel for his young brother’s body.

Finally, he felt Tristian’s shirt and he gripped it tight as he could and swam to the surface. When the Morton boys were no longer underwater, they each exhaled loudly and Tristian instantly cried. The cries told Ellis that his brother didn’t need CPR.

Coughing violently, Ellis struggled to breathe as he swam the two of them toward the shallow end of the plunge pool. When they got out of the water, Tristian ran and sat on a fallen tree, covering his eyes as tears dripped through his fingers.

Ellis walked toward the stump, before collapsing to the ground. On all fours, he coughed water onto the rocks.

“Ellis, are you okay?” Tristian asked, taking his hands off his eyes and looking at his savior. “Ellis? Are you okay?”

But Ellis didn’t respond. He kept coughing water onto the rocks.

* * * *

Long after the cheers, long after the interviews, and long after the flight across the ocean, Tristian was back in his quiet living room in his quiet town. The following day there would be a parade thrown in the small downtown, people lining along First Street to applaud the hometown hero. The mayor wanted to give Tristian a key to the city and the local newspaper reporter wanted to ask him a few questions.

But sandwiched between the chaos, Tristian stood in front of his fireplace. A framed certificate had hung there with pride for years: Ellis’ fourth-place finish at the state swimming meet. Tristian looked at it every time he passed by the fireplace – sometimes only a moment’s glance and other times he’d stand there and stare at it for minutes.

His Olympic gold medal was on the living room table because he needed to wear it later for the town festivities. But Tristian took the certificate from the greatest win of his life and put it in a frame. He pounded a nail eighteen inches to the side of his brother’s award, then he grabbed the Olympic certificate and softly hung it.

Thankfully, the Olympic committee didn’t print his birth name. Instead, they printed the name he used during his competitive career.

Ellis Morton

United States of America

First Place

100 Meter Freestyle

“It won’t bring you back, Ellis,” Tristian said to himself, as he carefully straightened out the frame. “But it’s the best I can do.”